Key points:

- Australia needs an ongoing, sustainable source of funding to improve our biosecurity system so it can protect our environment.

- A Frontier Economics report reveals ways to create sustainable funding for biosecurity, similar to the ‘polluter pays’ principle for air and water pollution.

- The 2023-24 federal budget announced a significant increase in biosecurity funding but more work needs to be done, especially around funding that will improve environmental biosecurity to protect nature.

Biosecurity is biodiversity’s best chance. If we don’t get it right, we will see our native plants and animals wiped out when the next deadly insect or disease slips through the cracks.

Whether travelling overseas or interstate, most Australians appreciate the critical job of biosecurity in protecting our environment and agriculture. But who pays for biosecurity?

Funding an effective biosecurity system is more than detector dogs and strong border quarantine. It’s about the preparations and long-term responses to major biosecurity threats like the current battle against red fire ants.

Yet right now, biosecurity funding is inadequate. It’s a hodgepodge that varies from year to year, targets only parts of the problem, and is not tied to the growing risk from global travel and trade. In short, it is inadequate.

Australia’s biosecurity system is too important to be trapped in yearly government budget negotiations. That’s why the Invasive Species Council – and many other bodies – are calling for a more sustainable biosecurity funding model to safeguard our way of life and environment.

And we’re not the only ones. Numerous reports have identified the need for a better, more sustainable funding model for biosecurity. We’re also seeking a model with dedicated funding for environmental biosecurity to properly protect our unique and diverse plants, animals and ecosystems.

Frontier report identifies new funding mechanisms

The good news? Implementing a Labor 2022 election promise, the federal agriculture department is currently reviewing biosecurity funding options with the aim of moving biosecurity funding to a more sustainable footing.

To assist them, the Invasive Species Council engaged Frontier Economics to conduct an independent assessment of biosecurity funding options. It identified seven possible mechanisms based on three targets:

- the party that created the issue (eg. importers),

- those who benefit from tackling the problem (eg. agriculture and tourism industries or the communities that benefits from healthy, pest-free environments), or

- the government.

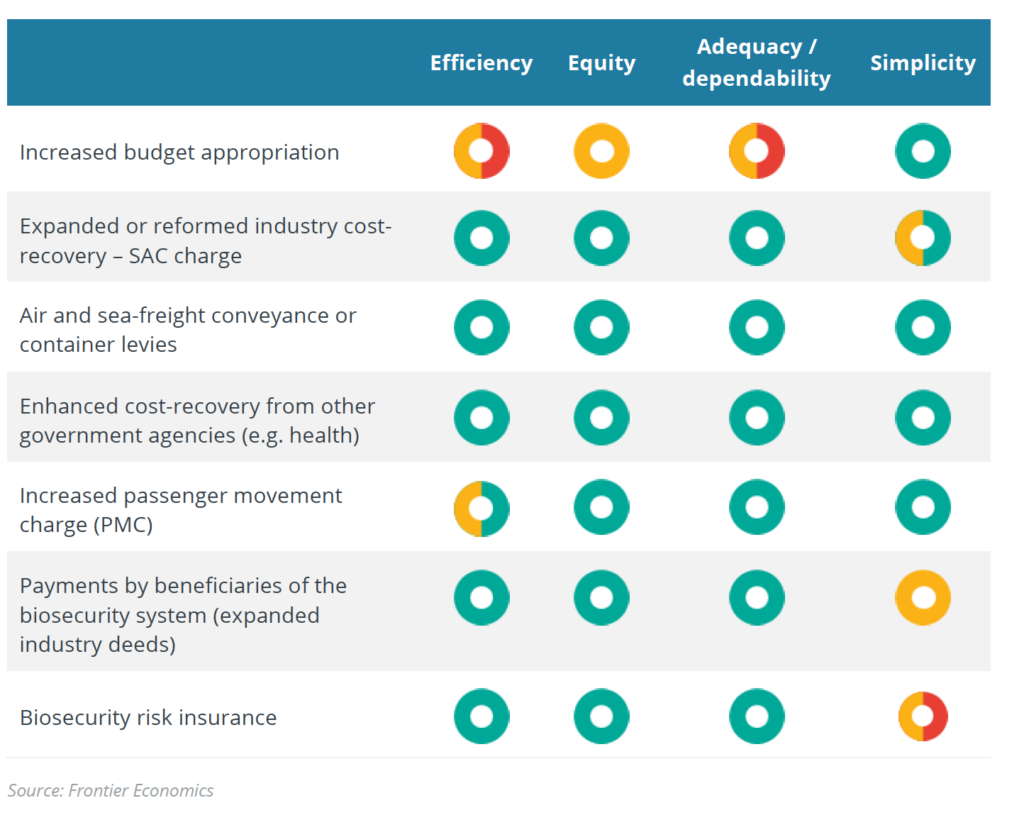

The review assessed seven potential funding mechanisms against four criteria based on well-established taxation and funding principles: efficiency, equity, adequacy/dependability and simplicity.

The seven funding mechanisms were rated with a traffic light system reflecting their success in meeting key aspects of the criteria.

The results indicate that the three leading options (with all green traffic lights) were:

- air and sea-freight container levies, and

- cost-recovery from government agencies (such as defence force deployments which pose a biosecurity risk to Australia through the movement of equipment).

In many ways, this is just common sense – those that create biosecurity risks should contribute to funding their impacts. It is similar to the well-established ‘polluter pays’ principle applied to the regulation of air and water pollution.

The Invasive Species Council is now urging the Australian government to utilise the report’s findings to break out of the current inefficient, ad hoc biosecurity funding model.

Because to achieve long-term environmental biosecurity outcomes that protect Australia’s animals, plants, environments and people, we must consider all available funding pathways and resource the biosecurity system properly.

First revenue-raising steps in the federal budget

Thankfully, the federal government is acting. The 2023-24 federal budget revealed the Labor government’s plan to deliver its election promise of ‘long-term, sustainable’ biosecurity funding.

It announced an increase in base-level government contributions (budget appropriations), with an immediate increase of $143 million in 2023-24 for biosecurity operations, rising to $255 million in 2027-28 and subsequently indexed to CPI. There was also new ongoing funding averaging about $10 million per year for Indigenous rangers carrying out biosecurity activities.

The budget also included four new charges:

- A new ‘cost recovery charge’ on air and sea imported freight valued at less than $1000 (currently exempt from import levies), expected to raise $27 million per year.

- Increases to other cost recovery fees for imported goods, expected to raise $36 million per year.

- A ‘biosecurity protection levy’ paid by local agriculture producers to partially recoup the benefit they receive from the biosecurity system, charged as a 10% increase on existing levies and expected to raise $48 million per year.

- A $10 increase in the passenger movement charge, levied on all overseas airline tickets, is expected to raise $160 million in its first year. However, this goes to consolidated revenue and is not guaranteed to support the biosecurity system beyond the usual budget cycle.

There will also be a review to consider increased cost recovery for international mail and military equipment and personnel.

Additionally, the container levy is back on the agenda. After the budget was handed down, federal minister for agriculture Murray Watt announced he is ‘seriously going to have a look’ at introducing a container import levy. This idea was first proposed in the 2017 Craik biosecurity review, included in two Coalition budgets and then shelved in 2020 with the arrival of Covid-19. Opposition leader Peter Dutton flagged his support for an ‘importer container levy’ in his 2023-24 budget reply.

A long road ahead for genuinely sustainable funding

In his post-budget speech, Minister Watt suggested the 2023-24 budget delivered sustainable funding for the biosecurity system. But this is far from reality.

Yes, the increase in government contributions will increase base-level operational support from the Department of Agriculture, and capture more fully the transactional costs of checking and processing incoming air and sea freight, passengers and mail. But the new measures will do little to recoup the direct costs of dealing with the invasive plants and animals that breach our border on arriving people and goods.

Without a container levy-style charge, there will be no mechanism for importers to collectively pay for the damage they cause or the preventative measures we urgently need. Currently, governments and local industries fund national surveillance systems, eradication programs, pest and weed containment and control measures, and the costly research and development needed to support these operations. The risk creators are free riders.

To ensure sustainability, any new revenue mechanism needs to be tied to the growing risk of imported goods and people. A container levy is a no-brainer. As the number of containers grows, so does the revenue.

Importantly, the new income measures in the budget failed to address the sustainability of funding for the states – the other half of Australia’s biosecurity system. They find it increasingly difficult to source the needed funds, especially smaller states like the Northern Territory, South Australia and Tasmania. This is becoming a concerning weakness in the system.

The special needs for the environment were also overlooked. There’s still no collaborative body tasked with preparing for the next invasive pest, disease or weed, and still no overarching environmental biosecurity response plan – whereas plans have been in place for agricultural industries for decades. There must be a dedicated revenue stream to guarantee this work occurs. An ideal target for a new biosecurity import levy to fund this would be environmental risk creators like the pet and aquarium industries.

One important announcement in the 2023-24 budget was that biosecurity funding would be more transparent. This will help us understand just how sustainable our biosecurity funding really is.

The 2023-24 federal budget moved us several important steps towards a more sustainable funding model for Australia’s biosecurity system. However, measures that will come closer to charging risk creators for the full cost of their damage, like a container levy or biosecurity risk insurance proposed by Frontier, are still just ideas being progressed by a poorly defined process. Unfortunately, the hard work still lies ahead, especially for the environment.

More info: