On 19 December 2022 the world finally landed on a new Global Biodiversity Framework under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The agreement, which aims to halt and reverse the decline in biodiversity globally by 2030, has been years in the making with negotiations heavily disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Striking the global agreement was no small feat given the uncertain geopolitical world that we currently face. The idea that 196 countries can find agreement on a plan to protect biodiversity for future generations should be celebrated.

For Australia, the CBD is more relevant than many people would appreciate. This is because Australia’s constitution is silent on which level of government is responsible for the management of the environment. However, following the famous Tasmanian dams case in 1983, the CBD provides the primary basis for the federal government to intervene in biodiversity matters through the constitution’s external affairs powers.

The new global framework is historic. It contains 4 goals and 23 action targets aimed at repairing humanity’s relationship with nature. There are a number of important and interlinked goals and targets across the framework. The one that has received the most attention globally has been Target 3, which proposes to protect 30 per cent of Earth’s lands and seas by 2030 through protected areas or other effective conservation measures.

There are targets that are focussed on drivers of biodiversity decline, such as invasive alien species (IAS), targets looking at enabling mechanisms, such as financial flows, and targets regarding the implementation of the framework. Importantly, there is a strong recognition of the role Indigenous people and local communities have in protecting and restoring biodiversity embedded throughout the agreement.

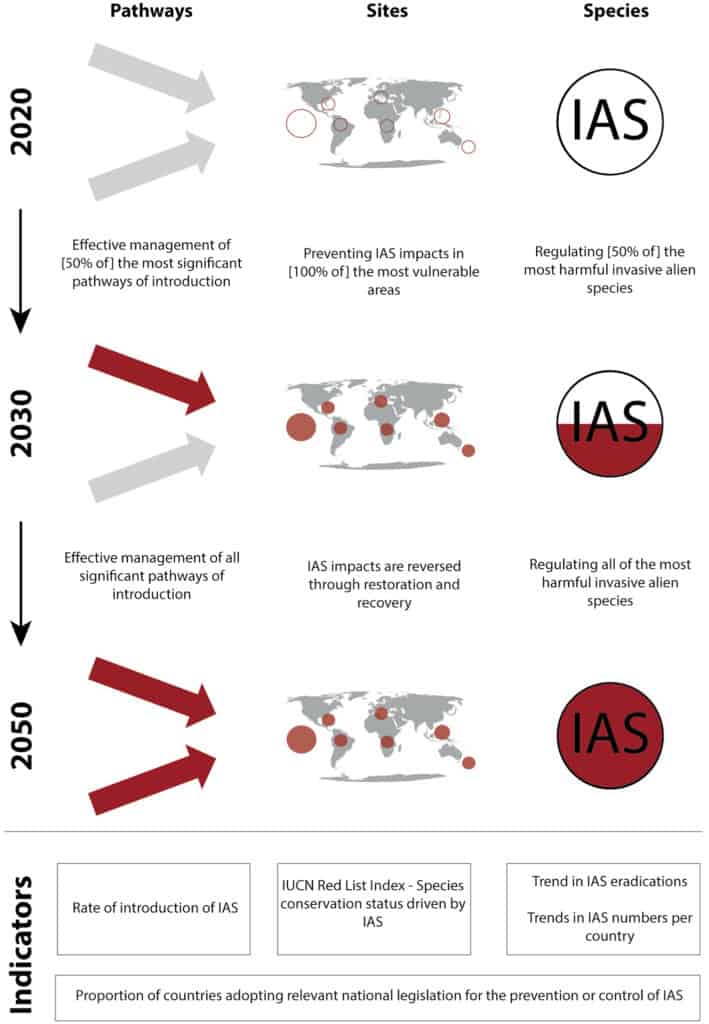

Unpacking Target 6 on managing the impacts of invasive alien species (IAS)

In the run-in to CoP15 there were some key papers that unpacked what a strong IAS target would look like and how to measure it. There were three key components that were put forward as being critical:

- Managing pathways that lead to the incursion of IAS

- Managing to protect against priority IAS

- Protecting key biodiversity sites most vulnerable to IAS

When you look at the final Target 6 text, it is notable that these three key elements have been included in the final target, meaning there is, at least, a strong scientific foundation from the outset.

Target 6

Eliminate, minimize, reduce and or mitigate the impacts of invasive alien species on biodiversity and ecosystem services by identifying and managing pathways of the introduction of alien species, preventing the introduction and establishment of priority invasive alien species, reducing the rates of introduction and establishment of other known or potential invasive alien species by at least 50 percent, by 2030, eradicating or controlling invasive alien species especially in priority sites, such as islands.

So what are the key components of the target?

- Identifying and managing pathways of the introduction of alien species: This is a broad statement that talks to national approaches to biosecurity. It lacks meaningful metrics which means it will be hard to measure or report against.

- Preventing the introduction and establishment of priority invasive alien species: This was an important inclusion late in the negotiations but provides a very strong impetus for a strong and well-resourced environmental biosecurity system. Key to this target will be mapping out the priority invasive species that need to be prioritised. The IUCN has developed the Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa (EICAT) which provides a useful basis for identifying priority invasive species on a regional basis. Australia currently has its own list of priority invasive species, the National Priority List of Exotic Environmental Pests, Weeds and Diseases, but doesn’t utilise the EICAT methodology. Delivering on this target will involve strengthening the approach to how we identify and prioritise environmentally harmful invasive species. Ideally the national priority list would be a live list that is updated regularly based on the best available information, with high levels of public transparency.

- Reducing the rates of introduction and establishment of other invasive alien species by at least 50 percent: This component of the target is measurable, but critics argued during the negotiation that the 50% figure was arbitrary. For this reason, the inclusion of the component of the target focusing on the prevention of priority IAS is so important. One of the challenges will be measuring the rate of establishment and spread of IAS, however recent papers have explored how to measure components of the target.

- Eradicating or controlling invasive alien species especially in priority sites, such as islands: This component of the target is broad and will require the identification of priority or high-value biodiversity sites to protect from IAS. This includes places like Mt Elliot, south of Townsville which is host to a large number of endemic native species, like the critically endangered Mt Elliot nursery frog. These endemic species are under imminent threat from the spread of highly invasive yellow crazy ants. This component of the target specifically highlights islands as areas of importance, noting the unique vulnerabilities of island biodiversity to invasive species impacts. In fact, all of Australia’s confirmed animal extinction events since 2000 have occurred on one of our islands, and the vast majority of those have been driven by invasive species.

You manage what you measure

Accompanying the targets is a global monitoring framework that sets out the headline and component indicators for each specific target. For Target 6 the headline indicator has been set for the rate of invasive alien species establishment. In an ideal world, this would be zero, but we know establishments will potentially occur.

There are a number of current examples of eradication efforts aiming to stop harmful invasives becoming established in Australia, including moves to eradicate the polyphagous shot-hole borer in Perth and red imported fire ants around Brisbane. It will be critical that both of these programs are successful for Australia to meet this target.

Table 1: Key indicators for Target 6

| Headline indicator | Component indicator | Complementary indicator |

| 6.1 Rate of invasive alien species establishment | Rate of invasive species impact and rate of impact Rate of invasive alien species spread Number of invasive alien species introduction events | Number of invasive alien species in national lists as per the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species Trends in abundance, temporal occurrence, and spatial distribution of non-indigenous species, particularly invasive, non-indigenous species, notably in risk areas (in relation to the main vectors and pathways of spreading of such species) Red List Index (impacts of invasive alien species) |

What does it all mean for Australia?

The new ambition embedded in Target 6 means that Australia is going to need to strengthen its environmental biosecurity system to make sure it can prevent, detect and respond with the required urgency to environmental incursions. That will mean making sure it is adequately resourced with sustainable, long-term funding. It will also mean safeguarding key sites from invasive alien species, whether that’s yellow crazy ants at Mt Elliot or feral horses in Kosciuszko. Lastly, Australia will need to dramatically improve the data it collects and how it monitors and reports on biosecurity and invasive species management across the country.

Our experience to date has been that environmental biosecurity information is not openly shared, and exists within opaque systems that are largely disaggregated. Governments will need to be more open and transparent in order to demonstrate any progress against this target. Overall, Australia will need to get much better at systematically managing invasive threats and developing more effective control methods if we are to meet Target 6.

It’s not about any single target, it’s all connected

There is no silver bullet to the global biodiversity crisis. The simple reality is that the threats to nature are interrelated and often compounding. You cannot safeguard nature alone by protecting 30% of the planet, as important as such a goal is. That is why there are 4 goals and 23 targets within the new global biodiversity framework. Each are critical to improving outcomes for people and nature.

In the second half of 2023 we are expecting a major report from the International Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, the primary scientific advisor to the CBD, on the global impact of invasive species. This will be a significant report that will set out the current status and trends of invasive alien species across the planet, their impacts, their drivers, their management, and options for policy to deal with the challenges they pose. It will be an important moment to highlight key management interventions needed to protect and restore nature.

For places like Australia, New Zealand and pacific island nations, invasive species have been one of the biggest drivers of biodiversity decline. These countries are also well-placed to have strong biosecurity systems to defend against new incursions. Target 6, and the broader framework, will play an important role in Australia’s domestic policy settings moving forward. Central to this will be organisations like the Invasive Species Council and the broader community making sure that the Australian Government meets the commitments it has signed up to in Montreal.

References

Essl F, Latombe G, Lenzner B, Pagad S, Seebens H, Smith K, Wilson JRU, Genovesi P (2020) The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)’s Post-2020 target on invasive alien species – what should it include and how should it be monitored? In: Wilson JR, Bacher S, Daehler CC, Groom QJ, Kumschick S, Lockwood JL, Robinson TB, Zengeya TA, Richardson DM. NeoBiota 62: 99-121. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.62.53972)