It’s not every day you can celebrate native species being removed from the threatened species list! But earlier this year, experts have concluded that 29 have recovered enough to be taken off, with native mammals making up up 15 of those species. Predation from feral cats and foxes was the key threat to most of the recovering mammals.

Their recovery is largely thanks to emergency interventions in the form of a relatively small network of islands and fenced havens where feral cats and foxes have been excluded, eradicated or at least substantially reduced in number.

While this strategy has proven invaluable to stave off feral cat and fox-driven extinctions and declines, it is far from a permanent solution if our aim is to restore thriving interconnected landscapes.

Beyond fenced havens

The larger challenge remains the sea of destruction wrought by feral cats and foxes beyond fenced havens.

The greater bilby and the burrowing bettong are two of the 29 native animals that have recovered well enough to come off Australia’s threatened species list. But both species used to inhabit over half the mainland. So despite being pulled back from the brink of extinction, they are still missing from most of their native ranges, along with the ecosystem services they provide. This is hardly a recovery.

Using AI to protect native species from cats and foxes

One of the most promising new tools in development that is helping to protect native wildlife outside predator-free havens is the Felixer.

These are solar-powered grooming traps that target cats and foxes with a small toxic gel bait. It has smart technology that automatically avoids firing on humans and other non-target species. The bait is later ingested by targets, particularly cats since they are habitual groomers and lick off the gel.

Thylation, the group behind Felixers, has now integrated camera-based artificial intelligence into newer models, on top of the existing LiDaR rangefinder sensors, to improve their target detection. Recent models have the functionality to avoid firing on any animal if they detect a bluetooth pet collar nearby. By affixing one of these bluetooth collars to pet cats and dogs, they can be safeguarded from being targeted.

Felixers have been deployed for research and testing purposes in numerous remote areas, and are quickly gaining attention as a new conservation tool for conducting highly targeted feral cat control with minimal non-target impacts. In February 2023, Felixers were registered for use across Australia, subject to state controls.

Do Felixers work?

Thanks to a very generous donation we have been able to partner with the Thylation Foundation to provide Felixers into critical habitats to support threatened species conservation and rewilding programs. One of those projects has been the recent deployment of Felixers to Arid Recovery, a 123 km2 fenced conservation area in northern South Australia. The reserve is home to native species like kowari and bilbies that are highly susceptible to feral cats and foxes.

In their first month of operation, 11 feral cats were verified as having been detected and 3 of those were targeted by a Felixer with a gel bait. The remaining 8 feral cats were not targeted because the device either wasn’t confident enough in its detection or wasn’t lined up to land the gel bait on the cat. While this means only 27% of detected cats were targeted, the Thylation Foundation says it expects an upcoming algorithm update will increase the success rate of firing the bait on detected cats to around 70%.

We can’t be sure exactly how many of the three feral cats that were successfully targeted then went on to ingest the gel bait and be removed from the ecosystem. And it will be a waiting game to see what longer-term impacts these feral cat removals have on the native wildlife in the area. But previous efforts can give us some insight into what we might expect.

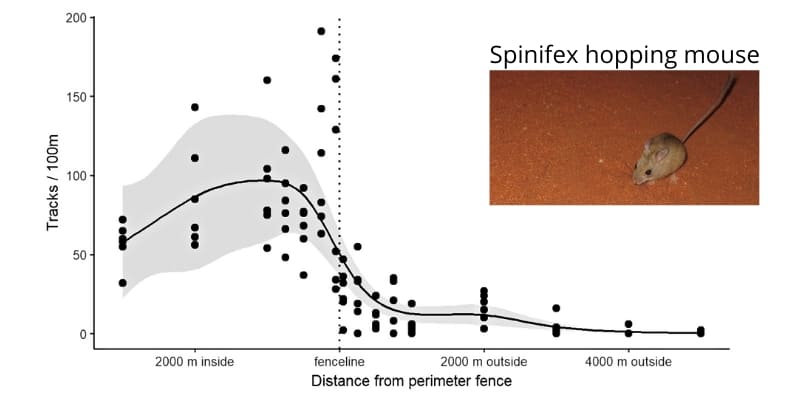

An earlier trial of Felixers at Arid Recovery successfully targeted 33 cats, with none of the cats that could be individually identified being detected again during the study period. By the end of the six week trial, the detection rate of feral cats had reduced by nearly two-thirds. None of the 1,024 non-targets like bilbies, birds, quolls, bettongs, lizards, kangaroos and humans were targeted by the devices.

Observations by ecologists on the ground suggest threatened kowari are already experiencing higher survivorship within the fenced reserve. Since the juvenile kowaris are small enough to disperse out through the fence where Felixers are now removing feral cats, we may begin to see increased survivorship outside the fenced reserve as well.

Elsewhere in Australia, early results show Felixers are already helping drive recoveries of native birds and giant geckos on Christmas Island and golden bandicoots in north-western NSW.

Adding Felixers to the toolbox

At a feral cat symposium in February 2023, Invasive Species Council campaigners heard how one of the major shortcomings of feral cat management across Australia is bureaucratic complexity. A confusing mess of legislation and protocols that differs between states, territories and even local governments means that most land managers are being prevented from being able to use tools that should be in their feral cat and fox control toolbox.

The NSW government bans the use of the PAPP-based bait Curiosity outside of National Parks and Wildlife Service lands. And the Victorian government has issued a blanket ban on the use of 1080 baiting to control feral cats, one of Australia’s most important tools for professional land managers. This, together with barriers preventing the testing of PAPP-based Felixers, means Victoria is also the only state or territory that prohibits the use of Felixer traps, even under research permits for conservation purposes.

While it is essential to ensure that all invasive species management is safe, humane and effective, it’s our native wildlife that will ultimately suffer the consequences if governments over-complicate approval processes and demand unreasonable conditions for tools to control feral cats and foxes. Tools like Felixer traps and the artificial intelligence plugged into them will only improve, and new tools will emerge. We can’t fall into the trap of letting regulations drag behind technological jumps in humane and effective feral cat control that can offer our native wildlife new opportunities to survive and recover.

To extend the recent recoveries we’ve seen in native animals like greater bilbies, burrowing bettongs and chuditches beyond introduced predator-free havens, we need to give land managers every effective tool that is available.

The recent conservation success stories on islands and within sanctuaries cannot allow us to ignore the deadly reality that awaits our native wildlife outside these havens. By combining trapping programs, landscape-level baiting and well-planned Felixer deployments, we can humanely and effectively release Australian wildlife from the pressures of feral cats and foxes that have already sent too many native species to an early grave.