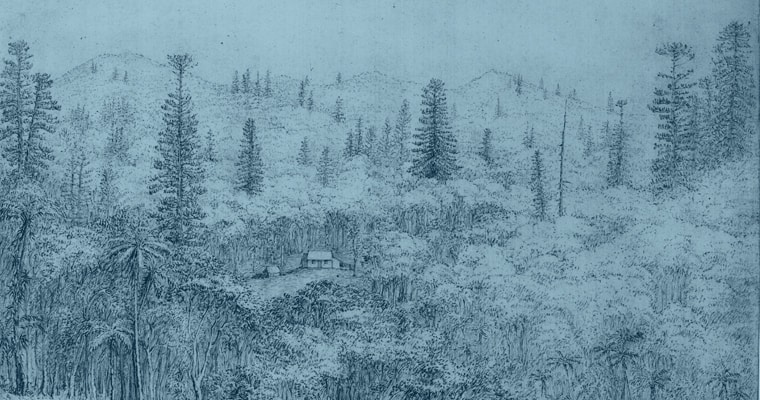

Barrow Island, a highly restricted nature reserve about 70 kilometres off the coast of Western Australia, is home to marsupials now extinct or threatened on mainland Australia as well as a rich diversity of plants and animals, some found nowhere else.

Twenty five kilometres long and ten kilometres wide, almost 2600 species have been regularly recorded on the island, including 378 native plants, 13 mammal species and at least 119 bird species. Ocean-going turtles, the flatback and green turtles, nest on the island.

Absent from that list are foxes, cats, rabbits, goats, black rats and domestic mice, which is why in 2009 the island was recognised as one of the largest land masses in the world with no established non-indigenous vertebrate species – no feral animals.

In contrast, nearby islands have up to a third of their area dominated by non-native flora, carry introduced rodents or have lost native mammals and birds due to invasive predators.

Gorgon gas project

In 2009 the West Australian Government controversially green lighted development on the island of the $54 billion Gorgon Project, a liquified gas plant that would become the largest infrastructure development in Australia’s history. Sounds like a recipe for disaster, right?

Permission for Chevron Australia and its joint partners to build their gas behemoth came with the proviso that they would run a comprehensive quarantine management system to protect the island’s biodiversity and result in no establishment of non-indigenous species.

They did so, and from 2009 to 2015 more than half a million passengers and 12.2 million tonnes of freight were transported to the island under the biosecurity system. Over six years 1.5 million hours were racked up carrying out inspections of freight and people arrivals. To date extensive surveillance has not detected the establishment of a single non-indigenous species during that process.

The gas project’s 3000 FIFO workers could not roam the island, bring pets or plants and are themselves subjected to the same strict quarantine measures that apply to each piece of mining machinery shipped to the island. Even fishing was banned.

Workers who spotted foreign matter, whether it was a seed, a snail or a cockroach, or identified a biosecurity failure, were publicly rewarded. Some even received a rare tour of the island outside the mine site. Adjustments were made in response to more than 140,000 hours of monitoring a year, 600,000 inspections and 7136 detections during the six year construction period.

Chevron’s successful biosecurity system on Barrow Island was a genuine ground-breaking effort that worked by applying adaptive risk-based thinking to all aspects of the operation. While the Invasive Species Council does not believe that operating effective biosecurity should be a green light for any development, we do want these practices adopted across the country. In areas of high conservation value, a system to meet the Barrow Island goal of no new non-indigenous species must become standard practice.

Whenever development expands close to undisturbed areas, it is imperative that good biosecurity is in place to prevent the loss of native plants and animals and avoiding a legacy of weeds and pests. While Chevron had major resources at its disposal, the challenge is to find ways to replicate this success with more modest means.

The successful implementation of the Gorgon quarantine system shows that biosecurity can be effective if well-resourced and provides a model for use in other high conservation value locations, especially on islands.

More info

This story is based on a scientific report published at nature.com and was written with the assistance of Andrew Burbidge who was a member of the Gorgon Project Quarantine Expert Panel.